Luis Martinez

August 15, 2024

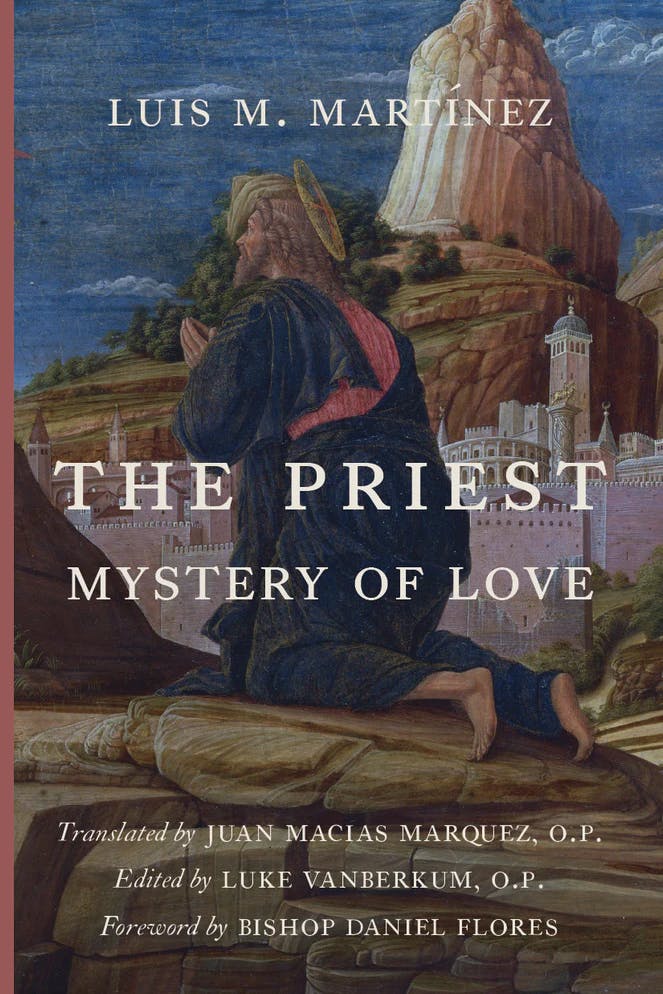

Luis M. Martinez, The Priest: Mystery of Love, Cluny Media, 2024, 278pp., $22.95, (pbk), ISBN 978-1685953225

Over the last few years, Cluny Media has retrieved classics of theology and literature for the English-speaking world. Their latest book, The Priest: Mystery of Love by Servant of God Luis M. Martínez (1881-1956) is a welcome addition to Cluny’s bookshelves, and an edifying text on the priesthood for clergy and lay people alike.

Martínez was ordained a priest at the age of twenty-three in 1904. He worked primarily in seminary formation until he was consecrated an auxiliary bishop of Morelia and then Archbishop of Mexico City and the first Primate Archbishop of Mexico on February 20, 1937. The book comprises 19 chapters, all of which are homilies or orations given by the Martínez, originally in Spanish. Chapter 1, “The Mystery of the Priesthood” stands alone and is the richest discourse in this book. Here, Martínez sets out several themes that recur throughout the other chapters: God’s special love for priests and the priest’s love for God, spiritual fecundity, and priestly suffering. Chapters 2-4 are homilies given at first Masses. Chapters 5-12 are homilies for anniversaries of first Masses, ordinations, and episcopal appointments for various priests and bishops. In chapter 13, Martínez eulogies the now venerable Antonio Plancarte on the centenary of his birth. Chapters 14-18 are funeral orations for various Mexican bishops and Pope Pius XI. In chapter 19, the book concludes with a discourse from Archbishop Martínez on the papacy.

The editors of The Priest: Mystery of Love did a great service to readers by beginning with Martínez’s discourse on the priesthood in chapter 1. Martínez’s reflection is based on Jesus’ resurrection appearance to his disciples at the Sea of Tiberias, especially in Jesus’ dialogue with Peter after the miraculous catch of fish. The themes from this chapter, and Jesus’ question to Peter, “do you love me more than these?” repeat throughout the book. Martínez structures the discourse in a threefold way, the priesthood as a mystery of love, a mystery of fecundity, and a mystery of sacrifice. Martínez speaks affectionately of Jesus’ singular love for priests: “Yes, he loves us more than the rest…If we knew how much he loves us!” (5). The priesthood is then “a mystery of love”: “Jesus asks of us our love, and of all the many great things a priest can do, the greatest is to love Jesus” (7). In presenting the priesthood as a mystery of love, Martínez counters an excessively functional notion of the priesthood: “if we love Jesus, from the abundance of our hearts our lips will speak, and from the plentitude of our interior life our exterior apostolate will flow” (7).

Perhaps most striking from the discourse of chapter 1 is the way that Martínez speaks of the fecundity of the priesthood, a dominant theme of the text. When Jesus says to Peter, “feed my lambs…feed my sheep,” he is inviting him into his own fecundity. Instead of “feeding the sheep” being a way that Peter demonstrates his love for Jesus, this instruction is rather a promise: “souls are not the trial that the priest has to bear in order to achieve the fulfilled joy of his love…No, souls are the earthly reward of priestly love and its eternal crown” (11). Martínez connects this mystery of celibate fecundity most especially to the sacraments of baptism, penance, and the Eucharist, but also to the preaching of the priest. Fundamentally the ability to give life is a reward for the priest’s love for Jesus, Christ’s response to “Lord, you know that I love you.” Martínez finally connects the mysteries of love and fecundity in the priesthood to the mystery of sacrifice. Suffering, says Martínez, “gives effectiveness to all our ministries” (20). This discourse is one that I have already made plans to read again.

The next chapters are homilies that Martínez gave at three first Masses. In each of these, Martínez connects the mystery of the priesthood to the liturgical celebration of that particular Mass. Martínez speaks of the priesthood in the mystery of the Ascension. He claims that the “center of the life and mission of Jesus Christ is his priesthood” and that therefore “all the mysteries of Christ have a priestly savor” (23). Both the priesthood and the Ascension deal with the fundamental pattern of exitus-reditus. The priest, like Christ, ascends to heaven and descends from heaven. This pattern is present in the Mass, and is also present in the life of the priest, who ascends to heaven in contemplation and descends to give to souls the fruits of contemplation.

Martínez likewise connects the Annunciation of Mary and the priesthood. The descent of the Holy Spirit on both Mary and the priest takes a two-fold quality of purity and fecundity. In Chapter 4 the Archbishop follows on this same theme of Mary and the priest. He speaks beautifully of the need for the priest to cultivate a relationship with the Blessed Mother patterned after the example of Christ. For priests, Mary is “our confidant in the interior life, our help in the apostolic life, our consolation at the foot of the cross” (59). At the heart of these three first Mass homilies is the conviction that all the mysteries of the Christian life are connected, but the priesthood especially “is a mystery that is in an intimate relationship with all the Christian mysteries” (51). No matter the liturgical occasion for a first Mass, Archbishop Martínez always finds the opportunity to speak about the gift of the priesthood.

While Chapters 2-4 address newly ordained priests with the scent of Chrism still on their hands, the next eight homilies point to a mature priesthood, which Martínez likens to an aged wine. The core of these homilies is the priest’ friendship with Jesus. This priestly friendship is characterized by the sharing of the secrets of love (cf. Jn 15:15). Martínez speaks of the four epiphanies of Jesus to the priest: the epiphanies are in the Gospel, in the tabernacle, in souls, and in the heart of the priest, and these epiphanies correspond to light, love, fecundity, and intimacy. The priest receives as a secret of love his own heart and mission and the heart of Jesus himself. So too these anniversary homilies speak to a “triumph over time,” Jesus’ faithfulness to the priest and the priests’ fidelity to Jesus. On the day of his ordination, the priest says with Peter, “Yes, Lord, you know that I love you.” And over 25 or 50 years of priestly ministry, this “yes” has grown richer (98). Martínez balances speaking of the ineffable gift of the priesthood with honest assessments of his brother priests and bishops. The priesthood is a treasure in an earthen vessel, a pearl set in crude metal (129). Even the fidelity of the priest is sometimes “haphazard.” But the humanity of the priest or bishop, rather than obscuring the transcendence of the gift, makes it stand out, for “there is nothing more divine than putting in our fragile vessels the treasures of heaven” (140).

In the funeral orations of Chapters 14-18, another common theme emerges: that of spiritual physiognomy. As every human person has a unique face with its unrepeatable expressions, even more each human soul has its own physiognomy. Martínez is especially interested in describing the spiritual physiognomy of each of the men he eulogies, all of whom were spiritual fathers to him. He characterizes their physiognomies by love of the Father, humility, tranquility, unity of life, and balance. Yet far from canonizing the men who he gives funeral orations for, Martínez above all appeals to the love of God and pleads people to pray for them. Speaking with tremendous admiration, the archbishop says that while “filial love” hopes that they are enjoying the beatific vision, “filial duty” demands our prayers (201). Martínez here provides a model for funeral homilies, speaking with great admiration and affection for his spiritual fathers, but placing their lives in the context of the Paschal Mystery and the purpose of the funeral liturgy.

My greatest takeaway from reading this collection from Archbishop Luis María Martínez is that this was a man who truly loved the priesthood. And from that, it is clear that he loved being a priest. The book's title, The Priest: A Mystery of Love is itself a fitting summary of the book. In his eloquent discourses, one gets a strong impression of Martínez’s love for the priesthood, and therefore a glimpse into God’s love for the priesthood. Here was a man who loved being a priest. The effect of these discourses was an increase in my own love for the priesthood. His love for the priesthood is so tangible on these pages that one cannot help but to experience the contagion of that love.

Much can be said about the various theological points that Martínez makes about the priesthood, but he also writes very beautifully. Martínez himself was a poet, and that comes through in each of the discourses. This eloquence is well-translated into English by Juan Macias Marquez, O.P.. Some readers could find his rhetoric overly flowery for a 21st century context, but the depths of suffering that Martínez endured as a bishop during the height of the Cristero War grant credibility to his pious language. Archbishop Martínez was a man of intellectual depth with a profound grasp of the tradition of the Church. Thus, this lofty language does not feel sentimental, nor saccharine, but flows from the depths of his own contemplative search for the physiognomy of Jesus the High Priest. I highly recommend this book to bishops and priests especially, but also to any lay people who desire to grow in their own appreciation for the mystery of love that is the priesthood.

Reviewed By: Fr. Noah Thelen, Pastor of St. Bartholomew Parish and St. Joseph Parish, Diocese of Grand Rapids, MI